Tag: Japan

The Maple Tree

Although it stills feels as hot and muggy as midsummer here in Washington, DC, it is actually the first day of autumn in the northern hemisphere. So, a painting and a poem in celebration. The leaves are changing color; we await those crisp cool blue-sky days. And wait… Happy Autumn, everyone.

The Maple with its tassell flowers of green

That turns to red, a stag horn shapèd seed

Just spreading out its scallopped leaves is seen,

Of yellowish hue yet beautifully green.

Bark ribb’d like corderoy in seamy screed

That farther up the stem is smoother seen,

Where the white hemlock with white umbel flowers

Up each spread stoven to the branches towers

And mossy round the stoven spread dark green

And blotched leaved orchis and the blue-bell flowers—

Thickly they grow and neath the leaves are seen.

I love to see them gemm’d with morning hours.

I love the lone green places where they be

And the sweet clothing of the Maple tree.

—John Clare 1793-1864

Elizabeth

February Festivals

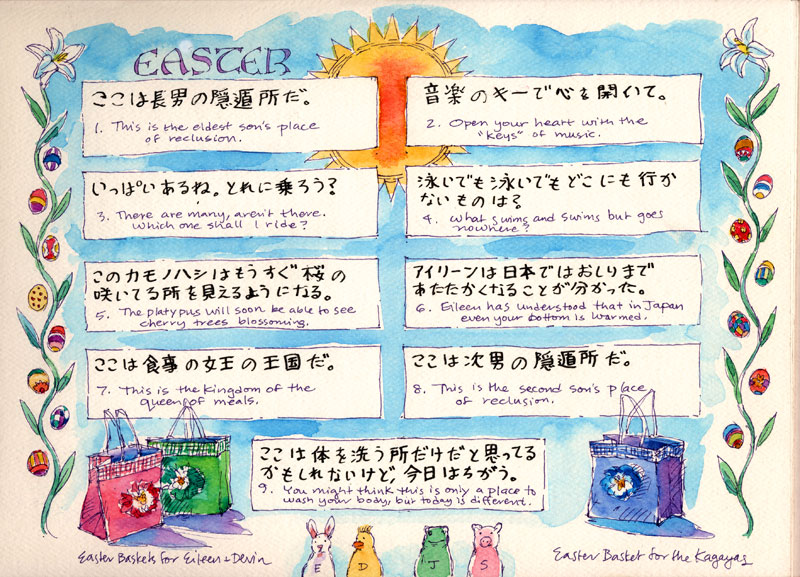

Easter in Japan

In Japan the school year begins in April—with emerging blossoms rather than falling leaves—and so, despite continuing difficulties, this past week children began their new classes, some of them amid vast stretches of earthquake and tsunami rubble.

A few years ago we spent this season with friends in Japan. With kindness, good nature, and interest, they found, and accompanied us to, an exceedingly long Easter church service. Afterward we transplanted to their home our family’s Easter basket treasure hunt, a tradition begun by my mother that I have continued with my own children. This time, though, the clues were bilingual, the English ones first written by me and then rewritten in Japanese by my son. (Later we copied the clues here into my travel sketchbook.)

Today is also the anniversary of the founding of the Library of Congress. For sketches and a saga, please see Library of Congress.

The Faces of Misfortune

The mind flinches as it tries to absorb the devastating succession of natural disasters that have taken place merely within the last few years. Hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico; multiple tsunamis in Indonesia; earthquakes in Haiti, Chile, New Zealand; innumerable floods, landslides, volcanic eruptions and wildfires. And now Japan, with scenes surreal of wreckage and relentless rushing waters and lives swept away—a triple whammy of earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear catastrophe.

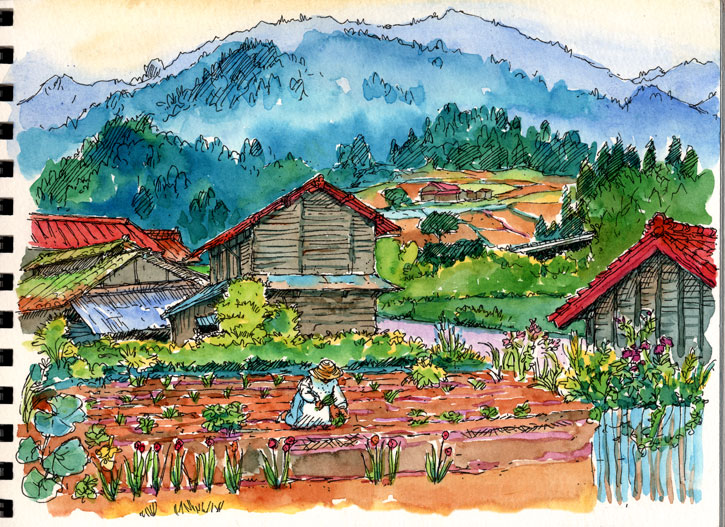

Here is a sketch from a visit we made to Japan when our son was teaching there. No matter where we went, total strangers were invariably kind, helpful, and generous, never hinting at the fact of our having dropped atomic bombs on them (the only country in the world to have suffered thus). On a walk one afternoon, we stopped to watch a woman working in her garden. Eventually noticing us, she invited us to see the rest of her garden—and her house—and meet her mother—and finally sent us off with just-harvested potatoes, radishes, and strawberries. This was absolutely typical of the entire trip.

I realize that politeness is a Japanese cultural value. There is a stiff-upper-lip quality that makes me think of stories about post-Blitzed World War II British (is there something about tea?), a characteristic that may lengthen the road to an American-style intimacy. But such sturdiness, resilience, and grace in the face of misfortune can be a blessing and a gift. Shikata ga nai.

The earth has grown so populous that natural disasters have enormous human impact, and simultaneously grown so connected that our common awareness of them is nearly instantaneous. The entire globe is now, truly, at our fingertips. It is theoretically possible to call up a picture of Anywhere, Earth, on the smartphone in one’s hand, if it has been visited by someone with a camera. And, thanks to international airlines (which actually used to be quite a speedy form of travel), many—through school or vacation or international aid organizations or family connections or business—have firsthand knowledge of worlds far from home. From knowledge, connection. We already carry the peoples and landscapes of the earth in our minds. The natural next step is the heart.

If you want to help, one way is to make a donation through the American Red Cross.

New Year’s Eve

When our son was spending his first New Year’s Eve in Japan, he reported to us on the local celebrations of this most important holiday.

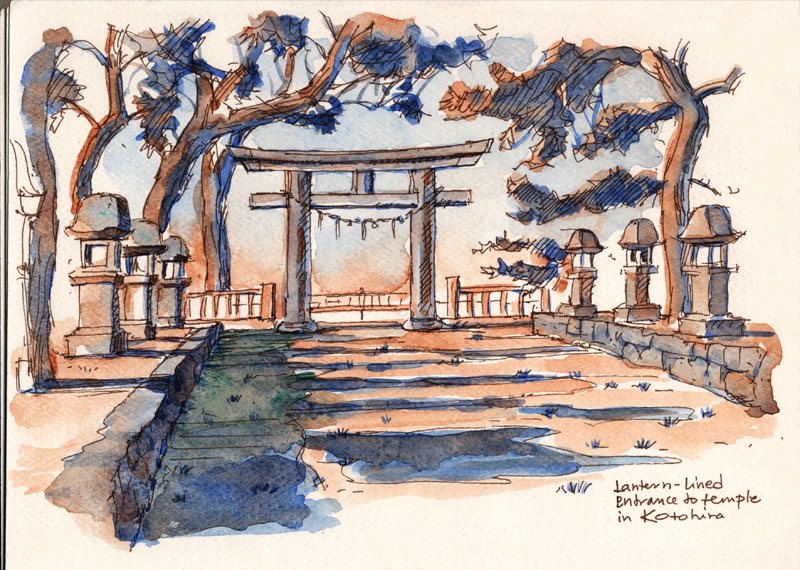

While we at home in the U.S. are staying up late to eat and drink, dance, and generally whoop it up with family, friends, and total strangers, in Japan the courtyards of shrines and temples are slowly filling with hundreds, even thousands, of patient, silent people waiting to make hatsumode—the first visit of the New Year.

On the stroke of midnight, all over the country, the doors open, and the temple bells begin to ring. And they ring for a total of one hundred eight times, representing the 108 sins (such as vanity, garrulity, prejudice, ingratitude, and unruliness) from which humankind must be freed before achieving nirvana. It’s part of a longer turning-of-the-year celebration during which people visit family, pay debts, eat special symbolic foods, and exchange gifts. (Although it seems that in Japan EVERY event—first trip to the dentist?—is an opportunity to exchange gifts.) What a contrast to Times Square, and beyond, where people are probably racking up those 108 sins right and left.

This is a sketch of a temple courtyard (but not on New Year’s Eve) from one of my Japan sketchbooks.

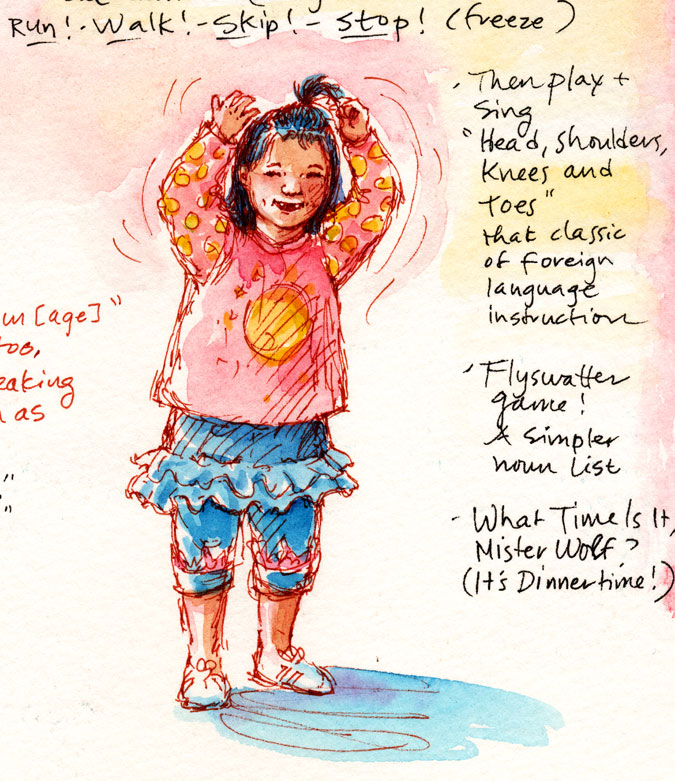

Shichi-Go-San

I don’t know what life in Japan is like for grown-ups, but for little children it looks pretty idyllic. Once young Japanese reach The Age of Reason, expectations for academic achievement and responsible, community-oriented behavior are quite high. But until then, Japanese (and other) children are cherished, admired, and doted-upon. Storekeepers, gas station attendants, and truck drivers keep handy stashes of sweets and tiny toys should some little one toddle by. Children are dressed in impossibly adorable clothes. Mothers are experts at the “distract and re-direct” method of discipline rather than giving the outright NO. It’s a world of bliss. When we visited our son during his stint of teaching in Japan, our daughter, then age eight, was so relentlessly and universally coddled that it’s a wonder she was willing to return home with her mean old parents.

Today is the Japanese autumn festival of Shichi-Go-San, which translates as “Seven-Five-Three.” It is a rite of passage for children. On this day (or the nearest weekend), girls age seven, boys age five, and boys and girls age three dress in traditional garb, perhaps for the first time (although this is unfortunately giving way to Western clothing) and visit Shinto shrines with their families to pray for good health and long life. Afterward the children are given “thousand-year-candy” packed in wrappers decorated with turtles and cranes, both symbols of longevity.

We weren’t visiting during Shichi-Go-San (although when I was seven and living in Japan I did attend the festival, appropriately attired in kimono and obi, but that’s another story). So I post this sketch of a little girl from one of my son’s classes, with the typical seven-year-old gap-tooth smile, playing one of their English-language games.

Demons Out! Happiness In!

In the northern hemisphere, early February is the season of festivals of light, spring, and beginnings, because of its placement approximately mid-way between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. Candlemas and Groundhog Day are but two examples. Another is the ancient Celtic festival Imbolc, named for the pregnancy and lactation of ewes, and celebrated with the lighting of fires in anticipation of the returning sun. In Japan the festival of Setsubun marks the beginning of the spring season, and this year, according to the old lunar calendar, it falls on February 3rd.

Given the numerous Japanophiles in our household, we are moved to celebrate Setsubun. First, we eat special sushi rolls containing seven ingredients—seven being a lucky number—in complete silence, while facing the auspicious direction for the year (in 2010 it’s sort of south-southeast) and making a New Year wish. After dinner we eat one roasted soybean for each year of our lives so far, pondering the memorable events. This alone keeps certain of us busy for some time. Then we toss the remaining soybeans out into the darkness and shout ONI WA SOTO! FUKU WA UCHI! to chase away wicked demons (and wary neighbors) and bring happiness. Some people (not us) also hang a fish head on the front door. Depending upon the kind of demon, I bet this is pretty effective.

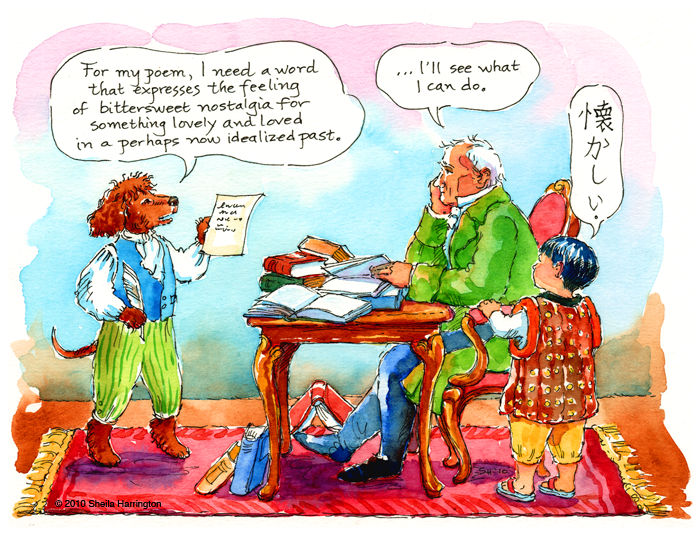

Man of Many Words

Today is the birthday of Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869), scientific writer, lecturer, and author of the Thesaurus, a project that he did not even begin to pursue seriously until his 70s. That ought to encourage the rest of us slowpokes. Roget was a lifelong and compulsive list-maker, a practice that apparently comforted him and helped sustain him through the terrible depressions that plagued him and his extended family, although he suffered tragedy enough throughout his life to justify serious despair. I love my Thesaurus and was inspired by this birthday to get on the library waiting list (speaking of lists) for a recent biography of Roget, Joshua Kendall’s The Man Who Made Lists. Among Roget’s many other admirers is J.M. Barrie:

“The night nursery of the Darling family, which is the scene of our opening Act, is at the top of a rather depressed street in Bloomsbury. We have a right to place it where we will, and the reason Bloomsbury is chosen is that Mr. Roget once lived there. So did we in days when his Thesaurus was our only companion in London; and we whom he has helped to wend our way through life have always wanted to pay him a little compliment. The Darlings therefore lived in Bloomsbury.” —Introduction to Act I of Peter Pan

Natsukashii: A Japanese word used to express the feeling described above. It is not yet in the Thesaurus.

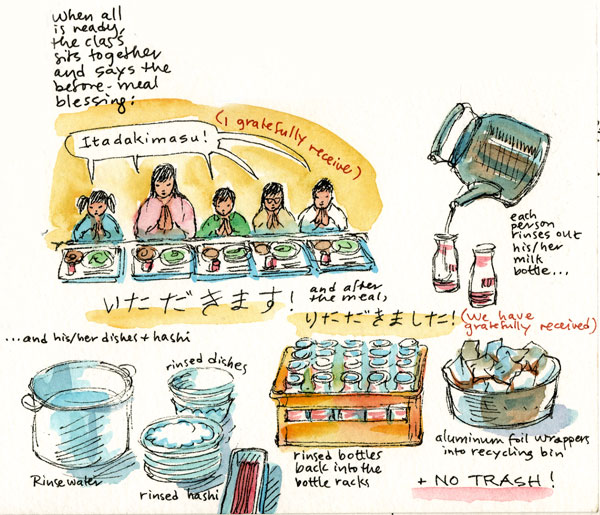

Green Lunch Part 2

(Continued from yesterday) We watched the children don cloth caps, masks, and aprons, help prepare and serve the food, and then clean up: scraping scraps into the compost bucket; rinsing plates, milk bottles, and chopsticks before they went off to be washed; crumpling aluminum foil and depositing it into the recycling bin. NO TRASH. Surely the schools of our nation’s capital city could do as well.

After lunch the children and teachers put on headscarves, took up mops and brooms, and went to do the daily post-lunch school cleaning. There’s your next proposal, Councilwoman Cheh!